If something can be done about it, What need is there for dejection? And if nothing can be done about it, what use is there for being dejected?

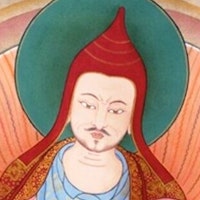

Shantideva

Way of Life

Topic: Wisdom & Understanding

If something can be done about it, what need is there for dejection? And if nothing can be done about it, what use is there for being dejected?

Shantideva

8th-century Indian philosopher, Buddhist monk, poet, and scholar

Life span

c. 685 - c. 763

Major philosophy

Mādhyamaka philosophy of Nāgārjuna

Place of study

Nalanda mahavihara

Shantideva, born around 685 CE in the ancient kingdom of Saurastra, now part of modern Gujarat, India, was a distinguished Indian Buddhist monk and scholar. He was the son of King Kalyanavarman and was initially named Śantivarman. Shantideva's early life was marked by auspicious signs and a deep inclination towards spirituality. Despite his royal lineage, he renounced his princely duties and chose the monastic life, eventually joining the prestigious Nalanda University. At Nalanda, Shantideva became an adherent of the Madhyamaka philosophy, a profound system of thought developed by Nagarjuna that delves into the nature of existence and the essence of enlightenment.

Shantideva's time at Nalanda was fraught with misunderstanding and controversy. His fellow monks perceived him as disinterested and aloof, often noting his absence from scholarly activities and practice sessions. This perception led to his nickname "Bhusuku," which implied that he only engaged in eating, sleeping, and idling. However, this view of Shantideva was dramatically overturned when he was challenged to give a public discourse. Rising to the occasion, Shantideva delivered "The Way of the Bodhisattva" (Bodhicharyavatara), a text that has since become a cornerstone of Mahayana Buddhist literature. This work, which eloquently addresses the virtues of compassion, wisdom, and patience, revealed his profound understanding and mastery of Buddhist teachings.

Shantideva's legacy extends far beyond his lifetime, which concluded around 763 CE. His teachings, particularly those encapsulated in the Bodhicharyavatara, continue to be studied and revered by Buddhist practitioners and scholars worldwide. The text's practical and philosophical insights have cemented Shantideva's status as one of the most influential figures in Buddhist history. His life and work exemplify the transformative power of inner wisdom and the enduring impact of genuine spiritual practice, offering timeless guidance that transcends cultural and temporal boundaries.

Way of the Bodhisattva

The Dalai Lama, and Desmond Tutu. The Book of Joy: Lasting Happiness in a Changing World. Edited by Douglas Carlton Abrams, Viking, 2016, pp. 333-334 [The Way of the Bodhisattva (Bodhicharyavatara)].

Shantideva

Theme: Wisdom

Commentary on Shantideva’s Statement [Commentary]

Shantideva, in “Bodhicharyavatara” (The Way of the Bodhisattva), says, “If something can be done about it, what need is there for dejection? And if nothing can be done about it, what use is there for being dejected?” This embodies a profound understanding of human emotions, particularly those of worry, anxiety, anger, and despair. By dividing life’s challenges into two categories—those we can change and those we cannot—Shantideva creates a simple yet profound guide to peace and equanimity. This approach encourages us to actively engage with our problems when we can influence the outcome, and to accept them with grace and patience when we cannot. It’s a philosophy that underscores the importance of discernment and mindfulness in our reactions to life’s vicissitudes.

Going deeper into Shantideva’s insight, it’s apparent how this philosophy aligns with the core teachings of Buddhism. It resonates with the idea of the Four Noble Truths, particularly the practice of right understanding and right effort. Understanding the nature of a problem (whether it’s changeable or not) and applying the appropriate effort (either taking action or practicing acceptance) can lead to liberation from suffering. In this sense, Shantideva’s wisdom is not merely a piece of practical advice but a spiritual practice that aligns with the path to enlightenment.

The Dalai Lama, a masterful interpreter of Buddhist philosophy, commented on this passage from Shantideva in “The Book of Joy: Lasting Happiness in a Changing World.” He explains that the wisdom in this quote is a reminder not to get upset about things beyond our control. Instead, recognizing our ability or inability to influence a situation gives us a clear path forward, either toward meaningful action or mindful acceptance. This teaching encapsulates an age-old wisdom that transcends cultural and religious boundaries, offering timeless guidance to living with greater peace, clarity, and joy. The Dalai Lama’s endorsement of Shantideva’s words reaffirms the enduring relevance of this teaching in our modern, ever-changing world.

Additional Shantideva Quotations

Related Quotes

Copyright © 2017 – 2026 LuminaryQuotes.com About Us