The Virtues We Acquire

Topic: Virtue, Morality, & Ethics

The virtues we acquire by first having actually practiced them, just as we do the arts. We learn an art or craft by doing the things that we shall have to do when we have learnt it: for instance, men become builders by building houses, harpists by playing on the harp. Similarly we become just by doing just acts, temperate by doing temperate acts, brave by doing brave acts.

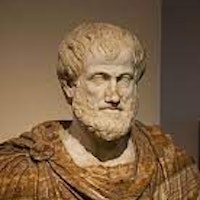

Aristotle (born 384 BCE in Stagira, a city in northern Greece – died 322 BCE in Chalcis, on the island of Euboea) stands as one of the foundational figures in Western philosophy and science. Born into a family connected to medicine—his father served as court physician to the Macedonian king Amyntas III—Aristotle was immersed from an early age in observation and inquiry into the natural world. At seventeen, he traveled to Athens to study at Plato’s Academy, where he remained for nearly twenty years. While he deeply respected his teacher, Aristotle charted his own course, seeking a more empirical and systematic approach to understanding reality.

His early works reflect both his gratitude for Plato’s vision and his conviction that knowledge must begin with experience.

After Plato’s death, Aristotle spent several years traveling, studying, and teaching. Around 343 BCE, he was invited by King Philip II of Macedon to tutor his son, the future Alexander the Great. When he later returned to Athens, Aristotle founded the Lyceum—also known as the Peripatetic School—a community devoted to research, teaching, and debate. There, he and his students examined every aspect of life, from logic, ethics, and politics to biology, rhetoric, and metaphysics. He classified knowledge into distinct disciplines and developed methods of reasoning that shaped scientific inquiry for millennia. His ethical writings, especially the Nicomachean Ethics, centered on the pursuit of eudaimonia: flourishing through virtue and the balanced cultivation of character.

Aristotle’s influence on philosophy, science, and education has endured for over two thousand years. His thought formed the backbone of medieval scholasticism and continues to inspire dialogue between reason, ethics, and the natural world. He saw human beings as rational and social creatures whose fulfillment lies in living thoughtfully and justly within community. For Aristotle, wisdom was not abstract speculation but a disciplined search for truth grounded in observation, dialogue, and the practice of virtue. His life and writings remain a testament to the enduring human desire to understand the world and one’s place within it.

Nicomachean Ethics

Wilson, Andrew, editor. World Scripture II. Universal Peace Federation, 2011, p. 569 [Aristotle, Nichomachean Ethics 2.1.4.].

Aristotle

Theme: Virtue Is

About This Aristotle Quotation [Commentary]

Aristotle writes, “The virtues we acquire by first having actually practiced them, just as we do the arts.” This comparison between moral virtue and artistic skill is central to his ethical teaching. Just as no one becomes a musician without playing an instrument, no one becomes just, temperate, or brave without doing just, temperate, or brave actions. Virtue is formed by action. It is not something given or innate but something shaped by what we repeatedly choose to do.

He continues, “We learn an art or craft by doing the things that we shall have to do when we have learnt it.” A person becomes a builder by building, and a harpist by playing the harp. This logic, Aristotle says, also applies to character: “we become just by doing just acts, temperate by doing temperate acts, brave by doing brave acts.” The moral life is not defined by beliefs alone, but by what is done—deliberately and consistently. The emphasis remains on practice, not possession.

This sequence—doing first, becoming second—places responsibility on each individual. The theme that virtue is learned through practice offers a clear path forward. By choosing to act justly, with temperance, or with courage, a person becomes just, temperate, or brave. Aristotle’s words remind us that virtue is not a fixed trait but something made and remade through daily effort.

Aristotle, Nichomachean Ethics 2.1.4. [Additional Commentary]

writes, “The virtues we acquire by first having actually practiced them, just as we do the arts.” Virtue, like any craft, is learned through action. “We learn an art or craft by doing the things that we shall have to do when we have learnt it”—a builder builds, a harpist plays, and a person becomes just, temperate, or brave by doing just, temperate, or brave acts. This sequence—doing first, becoming second—shapes Aristotle’s understanding of virtue as something formed through practice, not something given or innate. The emphasis is not on theory but on repetition.

His words, “we become just by doing just acts, temperate by doing temperate acts, brave by doing brave acts,” provide a simple and clear framework for ethical development. For Aristotle, character is shaped by action, and action is shaped by the habits we form. This approach places responsibility with each individual and offers a path that is available to anyone willing to engage it. In this light, virtue is not a fixed state but a practice shaped by choice, effort, and repetition.

Related Quotes

Copyright © 2017 – 2026 LuminaryQuotes.com About Us