Of all that we feel and do, all the virtues and all the sins, love alone crowds us at last over the edge of the world.

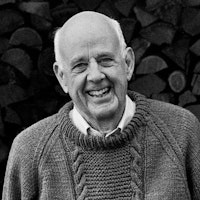

Wendell Berry

The Edge of the World

Topic: Life Beyond Death & the Spirit World

But love, sooner or later, forces us out of time. It does not accept that limit. Of all that we feel and do, all the virtues and all the sins, love alone crowds us at last over the edge of the world. For love is always more than a little strange here. It is not explainable or even justifiable. It is itself the justifier. We do not make it. If it did not happen to us, we could not imagine it. It includes the world and time as a pregnant woman includes her child whose wrongs she will suffer and forgive. It is in the world but is not altogether of it. It is of eternity. It takes us there when it most holds us here.

Wendell Berry was born in Henry County, Kentucky, on August 5, 1934. This region has not only been his lifelong home but also the inspiration for much of his writing. He grew up understanding the rhythms of the land, a knowledge that would deeply influence his roles as both a writer and a farmer.

He has produced a diverse range of works, spanning poetry, essays, and novels. A consistent theme across his writing is the connection between humans and nature, informed by his firsthand experience working on his Kentucky farm. As an academic, Berry taught English, further establishing his foothold in the literary community.

Beyond his personal achievements, Berry's family has played a significant role in his life. His close relationships, especially with those who share his ties to Kentucky, have further anchored his love for the land and community. While he has been a voice for sustainable farming and conservation, his writings also often touch upon the intricate dynamics of family and community life in rural America.

Jayber Crow

Berry, Wendell. Jayber Crow. Counterpoint LLC, 2000. [—Wendell Berry, Jayber Crow].

Wendell Berry

Theme: Love

About Wendell Berry’s Quote [Commentary]

Jayber Crow, Commentary by Andrew Petiprin [Excerpts]

Resources

Related Quotes

Copyright © 2017 – 2026 LuminaryQuotes.com About Us